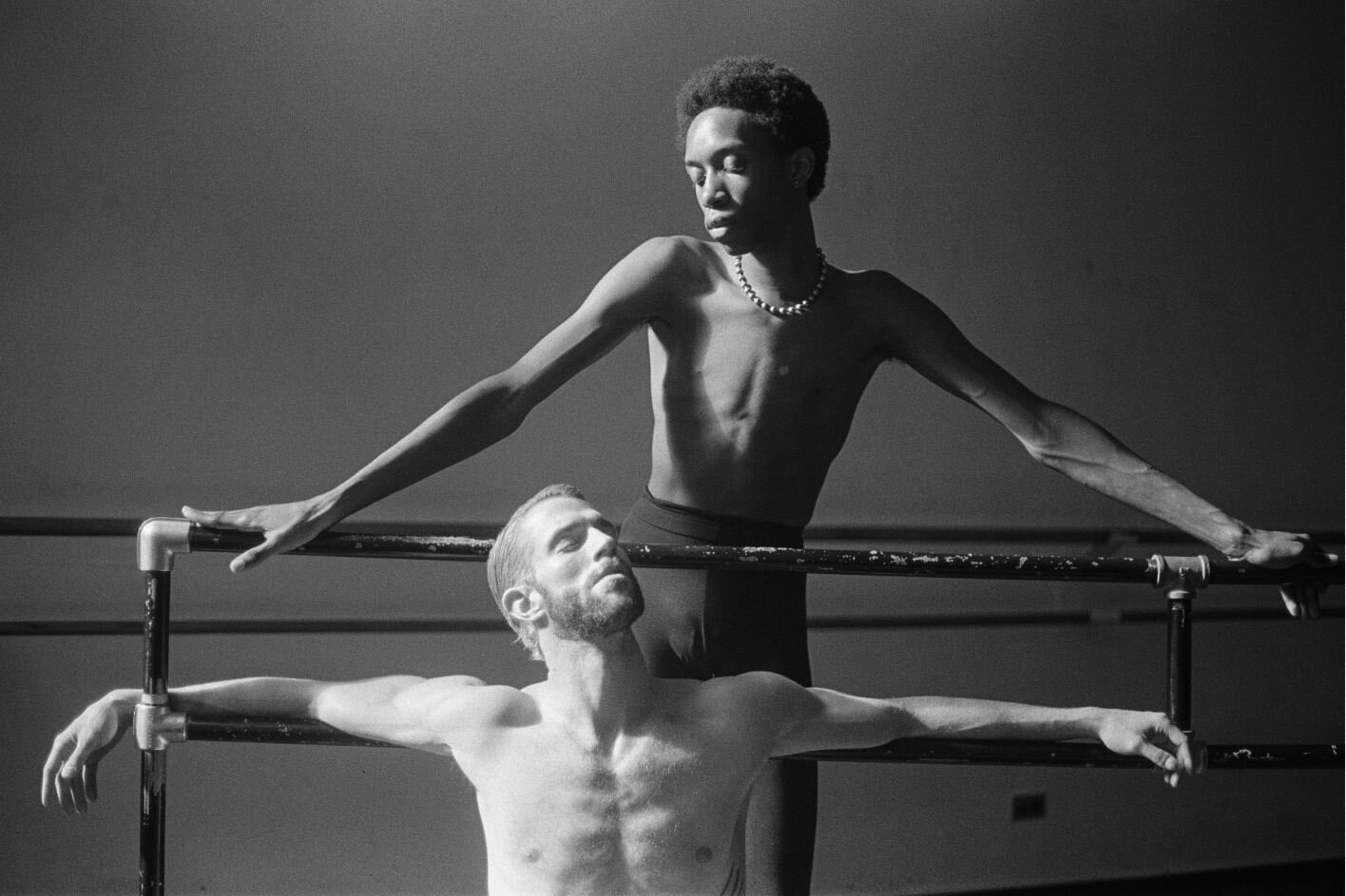

“BALLERINO” SOLO SHOW OF PHOTOGRAPHER DAVID-SIMON DAYAN OFFERS AN INTIMATE, GRACEFUL TAKE ON THE LIGHT AND THE CONTRASTS AMONG MEN IN BALLET

Born in Los Angeles, David-Simon Dayan uses photography and poetry to challenge the notions of gender and masculinity being presented to him. In his interview with A Book Of, we chat about how he uses both mediums to express these questions, utilizing the crafts to further understand himself and the larger queer community. With his first solo show, Ballerino, the artist invites the viewer to understand the experience of men in ballet by providing an intimate peak into their time at the barre, utilizing harsh light that falls on hardened, yet graceful bodies; the result, a timeless portrayal of the human form.

Photography by David-Simon Dayan

Your photographs in Ballerino read as though they’re in a rehearsal, even though sometimes they’re looking straight into the camera, almost inviting the viewer to watch them. In this way, your work often carries a quality of spontaneous intimacy. Do you search for these particular moments? Do you stage them?

Often, I do search for them, or rather, they’re presented to me, and it’s up to me to be able to catch them, to be quick with my camera. In this case the images were all staged, at least, mostly. I met with these dancers in various studios that provided what I perceived as breathtaking settings, and asked that they bring certain traditional pieces to wear, plus any accessories they might feel comfortable in. The nature of dance, specifically ballet, doesn’t necessarily embrace individualized expression within a group, so a pearl necklace, for example, would be about the extent possible. What sparked the series, at least visually, was Mapplethorpe’s work, namely, Two Men Dancing, so I ventured out the day before on a hunt through New York City to find crowns that felt right. Light is vital, then composition, but once they were set in their places, it was equal parts directing and interacting. With two of these dancers, it was our first time meeting one another, so it was important to me that they felt comfortable, so sometimes the camera drops, and you just get to interact with this human, and the moment is beautiful. It truly is a matter of connecting, and photography invites that moment to take place.

And all of these images from your solo exhibition were shot on film, weren’t they? When did you begin shooting film?

They were all shot on my most treasured film camera. I have collected a few now, but my A-1 is the first one I purchased from a shop in downtown Manhattan. I had been shooting exclusively digitally at that point, mostly without direction or purpose. You know, when I first picked up a proper camera, film was well on it’s way out. But I’ve noticed, it’s had a resurgence because the craze of technology over all has settled a bit and people like myself are interested in the rawness film offers, in the patience of the process. It’s more of a practice in being present, and in trust, mostly. Sometimes you learn a hard lesson, though, when either you’ve made a mistake or you think “this long-expired roll I bought off a street vendor will be fine,” and it very well might be, or it might drastically stray from what you were expecting, effectively ruining your plans. But we learn.

Photography by David-Simon Dayan

The juxtaposition of masculinity and femininity are prominent topics in your works. What’s your take on the expression of gender?

The construct of gender is slippery, to say the least. As it relates to my upbringing, and many others, it’s cemented as two forms, really, two options. But when you realize you don’t necessarily fit into one of those two forms, you have trouble relating, you seek something outside of what’s being presented, what’s being marketed to you. In the culture I was raised in, men pursuing careers in dance wasn’t really an option. I loved to dance, though, and did it briefly in school, along with my almost exclusively female friends. But as time goes on, we realize it’s not a so much a matter of one or the other, or so you’d hope. And at this time, at least, I’m not necessarily interested in presenting certain heteronormative macho ideals that are rife in photography. Arnold Schwarzeneggar photographed shirtless on a white horse by Annie Leibovitz is a brilliant image, and all her work with him documented a certain reality with skill that’s deserving of respect and recognition. That said, I always make sure to ask the subjects I work with to express something, even if a minor gesture of the hand, that somehow subverts the traditional molds. And I’m grateful to work with individuals who already do so in their own respective ways.

Photography by David-Simon Dayan

In addition to your photographic work, your poetry has also been featured in A Book Of. How did you find yourself writing poetry? Do the two relate?

They absolutely relate, they’re varying expressions of certain questions, ideas, or experiences I have. The first poem I remember writing was years ago, at a time when I was already reading constantly, and found myself relating to these grand ideas of love, of intimacy and tragedy. And I had a fleeting affair with someone who’s breath left me yearning for the taste of tobacco. It sounds silly, doesn’t it? But then heartache, who would have guessed, led me to writing again recently, when I felt alone and anxious, and I didn’t know how to get these feelings out, so I begun quickly writing these poems without thinking much of them. They were for myself and myself only, they felt so private. But then I shared some of them online, and people reached out expressing their gratitude, and suddenly I had strangers sharing intimate experiences with me, about finding out their partners’ affairs and the abrupt ending of their partnerships, and I realized that these private matters are actually, of course, universal, and isn’t that meaningful? We’re all made of the same ingredients.

In these images, along with much of your work, intimacy and sexuality seem to play a role. Is this a conscious choice?

Well, yes. When sexuality is an extremely present force in your life, art can aid in the exploration and understanding of it. Photographers often photograph their lovers. The craft of portrait photography is inherently intimate. It can be voyeuristic, as you mentioned, requiring of an invitation, and without the exchange between artist and subject, what would remain? Both parties are necessary. I’ve met some beautiful couples that I found extremely inspiring, like James Whiteside, who’s in this series, and his boyfriend Dan, otherwise known as Milk, who you might recognize if you’re a fan of Drag Race. And if you’re not, well, you should be. And spending the afternoon shooting them was something I’m really grateful for. Or my dear friend Marlaine and her now fiancé, Amy. I didn’t see many queer couples growing up, and sometimes it’s a matter of safety for people, choosing to remain private, but the impact of sharing your love, even more so when it might seem unconventional, is vital if it might somehow aids in someone’s self-acceptance.

Photography by David-Simon Dayan

With your first solo show featuring exclusively male ballet dancers, I wonder, how did you start photographing dancers?

Well, as we touched on earlier, the show began as not only an homage to Mapplethorpe, who’s work made ripples through the field and world during his time, but also a conversation I had with the subjects who were already friends. At the time, I was taking ballet classes a couple times a week. And I’m awful at it, but that’s beside the point, hahah. But they were describing their experiences in the professional realm of ballet, and that all came together when I learned how certain expectations within the field were surprisingly insensitive to it’s participants, so it became a story, really. And I had to photograph that.

Throughout your work, the human form seems to be a focus, with sensuality being celebrated. Would you agree?

It absolutely is. The human form holds a power capable of such excellence. The potential energy of dancers is breathtaking. They’re without doubt the subjects I’ve had most pleasure from working with. Their ability to translate thought and sound into movement is nothing short of captivating. With regard to sensuality, maybe that is more subconscious, but yes some of my work might be perceived as erotic. Sometimes more blatant than others, but in this case, maybe that’s a natural response to the masterful feats of these subjects.

Photography by David-Simon Dayan

What advice might you give to a emerging photographers?

Am I qualified to answer this? But I’d say just shoot everything. Learn technique and then you can decide what works for you. Maybe you’ll know why it is you want to shoot in the first place, or maybe you’ll learn as you do. And with any creative profession, try not to take anything too personally or view your work as sacred. Everyone can always improve, expand, and continue to challenge themselves.

Photography by David-Simon Dayan

*Due to safety precautions, the opening of Ballerino has been postponed, but once confirmed, the article will be amended to reflect the correct opening date. It will take place at A Love Bizarre in Los Angeles, Ca.*

Photographer David-Simon Dayan